The eye is a fascinating part of the human body. It is uniquely composed of transparent structures so as to allow light to enter. This transparency allows eye doctors to directly observe the optic nerve, which is actually a part of the brain. What may surprise many is that the brain, the eye and the optic nerve all originate from the same group of embryonic cells during gestation.

During this period, the cells destined to become our brain extend two thin tubes of tissue that eventually form the eyes and optic nerves.

This ability to examine the inner structures of the eye, and observe how systemic conditions affect the nerves and blood vessels of the eyeball is why the eye is often referred to as a “window” to our overall health. Through a combination of photographs, scans and artificial intelligence (AI), ophthalmologists and researchers aim to use this “window” to predict the risks of heart attacks and strokes, and even to detect signs of dementia before a person is aware of it.

LINKING THE BODY TO THE EYE

Lining the inner surface of the eyeball is a thin membrane called the retina. The retina is composed of light-sensing cells situated beneath layers of incredibly delicate nerve fibres – so fine that they are transparent to the naked eye.

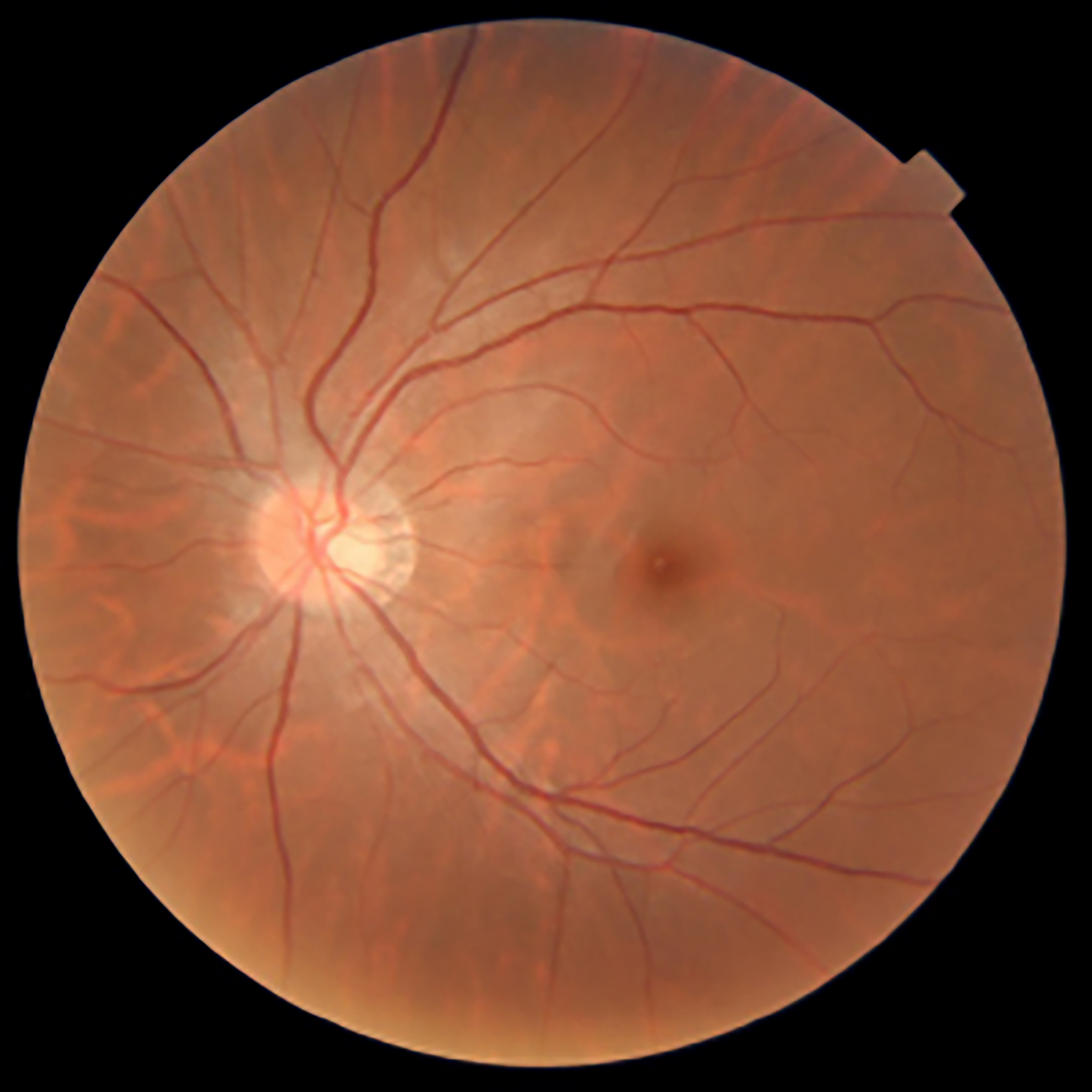

Figure 1: A retinal photograph of a healthy left eye. The fine blood vessels emerge from the yellow optic nerve, which connects the retina to the brain.

These nerve fibres converge to form the optic nerve, which also gives rise to the network of blood vessels that nourish the retina

(see Figure 1).

While intrinsic eye diseases can damage the retina, conditions originating from outside the eye can also cause harm. For example, poorly controlled diabetes can lead to bleeding in the retinal blood vessels, resulting in a condition known as diabetic retinopathy.

If high blood sugar is damaging the vessels in the eye, it stands to reason that the fine blood vessels in other parts of the body, such as the heart or kidneys, may also be affected. Conversely, could heart problems or kidney disease manifest as tell-tale signs in the eye?

Ophthalmologists and researchers have long pondered the connection between eye health and overall health. Manually correlating the appearance of blood vessels in the eye to a patient’s medical condition has been a daunting task. The breakthrough came with advances in AI, specifically in the field of “deep learning.” Deep learning uses computer algorithms to learn from large amounts of data (similar to how humans learn from experience) without the need for explicit programming or instructions. With sufficient computing power and data, these algorithms excel at specific tasks, one early example being distinguishing between photographs of cats and dogs!

Given the close relationship between the retina and the brain, researchers are exploring the use of OCT images to detect brain- based diseases such as dementia. Dementia is a broad term for conditions that result in progressive loss of memory and reasoning skills.

Researchers first applied deep learning to retinal photographs of diabetic patients. By leveraging a large database of images, they trained algorithms to identify diabetic retinopathy from these photographs, achieving accuracy rivalling that of trained ophthalmologists in a fraction of the time required for a traditional eye examination.

Building on this success, researchers explored using retinal photographs to screen for illnesses beyond the eye, such as heart disease and kidney failure. Deep learning algorithms have been able to correlate subtle changes in retinal blood vessels with the presence of heart disease (such as calcium deposits in heart vessels) and predict a patient’s risk of suffering a heart attack within five years.

Other studies have shown that these algorithms can estimate a patient’s kidney function from a retinal photograph or predict the risk of developing kidney failure in the future. These advancements suggest that a simple photograph of the eye could enable doctors to diagnose various conditions without the need for blood tests or expensive, time-consuming scans.

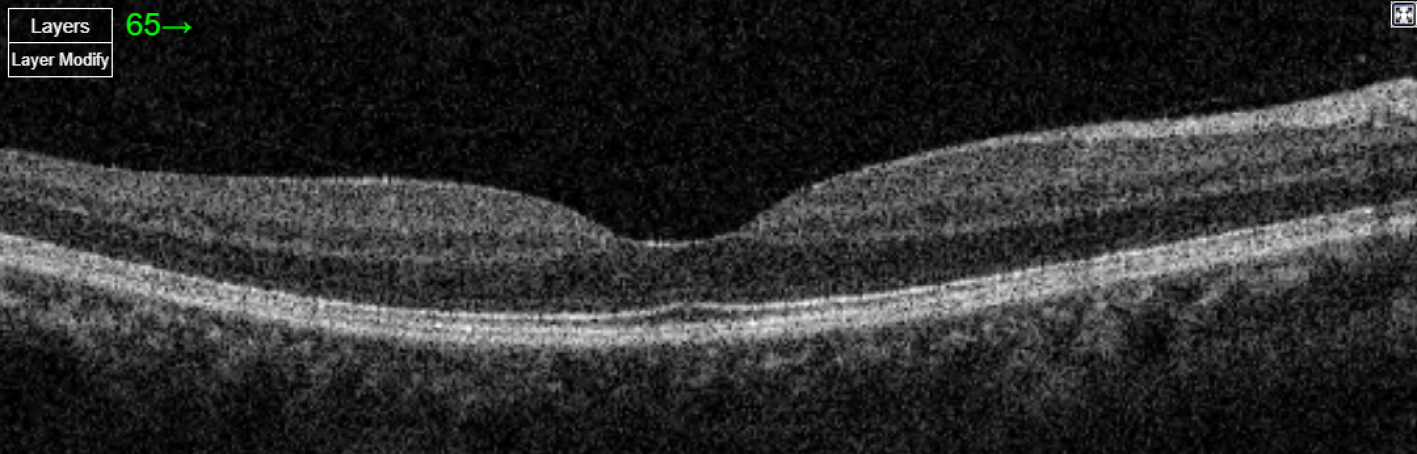

Retinal photographs are not the only imaging method used by ophthalmologists. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a high-resolution imaging technique that uses high-speed lasers to scan the retina tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of times per second. The precision of these scans is remarkable, with a resolution between 5-10 microns – approximately 10 times finer than a human hair (see Figure 2 next page). With OCT, ophthalmologists can examine the intricate layers of the retina to identify conditions such as age-related macular degeneration and glaucoma.

Given the close relationship between the retina and the brain, researchers are exploring the use of OCT images to detect brain-based diseases such as dementia. Dementia is a broad term for conditions that result in progressive loss of memory and reasoning skills.

Patients can become disoriented and experience personality changes. It is important to note that these symptoms are not a normal part

of ageing but are caused by illnesses.

Figure 2: A scan of the retina, performed by an optical coherence tomography (OCT) machine. The scan shows the many fine layers of the retina as black, white and grey layers.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia. Currently, Alzheimer’s is diagnosed using specialised tests, such as positron emission tomography (PET) scans to look for abnormal protein deposits in the brain, or lumbar punctures (drawing fluid from the spinal cord) to check for proteins specific to Alzheimer’s.

However, neither test is suitable for screening large numbers of people. Lumbar punctures are invasive and carry risks, while PET scans are costly and require specialised equipment that is not widely available.

Deep learning algorithms trained on thousands of OCT images have identified differences between the eyes of healthy individuals and those with Alzheimer’s disease. Patients with established Alzheimer’s show significantly thinner retinal nerve layers, with a distinct pattern of thinning in certain retinal areas.

Some studies suggest that otherwise healthy patients with thinner-than-average retinal nerve layers may be at higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s in the future. Additionally, some forms of OCT can measure blood flow in retinal vessels. Studies have shown there that is reduced blood flow in the eyes of Alzheimer’s patients compared to healthy individuals.

AN EYE SCAN FOR YOUR HEALTH?

Diagnosing and predicting heart disease or dementia from a retinal image is still largely in the research phase, as many questions remain unanswered. For instance, will the AI algorithms that make these predictions work well across different populations?

Algorithms that perform well with light-coloured Caucasian retinas often prove less reliable with the darker-coloured retinas of Asians. Additionally, these algorithms are typically trained on images from patients with a single, well-defined illness.

In reality, patients often have multiple co-existing conditions, such as diabetes, high blood pressure and heart problems, which could confuse an algorithm looking for signs of dementia in retinal blood flow. Another challenge lies in ensuring these algorithms can work with photographs and scans from different machines and manufacturers, avoiding restrictions to proprietary devices.

It will take months and years of continuous evaluation before researchers, doctors and regulators are convinced that these algorithms are accurate enough for everyday use.

Nonetheless, the time will soon come when the ability to diagnose and predict our current and future health may be just an eye scan away. PRIME

Leave A Comment