Getting the Basics Right

Mental health is one of the fundamental pillars of an individual’s health and wellbeing; yet, it is often overlooked or neglected. Even when acknowledged, it is more often than not relegated to something of little significance for reasons such as lack of awareness and understanding, ineffective mental health policies and intervention, budget constraint, discrimination and stigma (Ngui, Khasakhala, Ndetei & Roberts, 2010). In addition, it often slips off our radar as it is not as visible as physical health; a broken arm or the presence of cancer cells are more directly observable.

When a government is facing a tight budget, a situation that is not uncommon in developing nations, resources available for the promotion of mental health are likely to be scarce. In most developing countries, only less than 1 per cent of the already low healthcare expenditure is channeled towards mental health (Goldberg, Mubbashar, & Mubbashar, 2000). Yet, mental and substance use disorders accounted for about 7·4% of disease burden worldwide in 2010, and this rate continues to rise in developing countries. As such, mental health policy and services research are necessary to identify effective methods to alleviate this problem.

A clear understanding of mental health is the key for us to find the best solutions. Mental health, as defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO), is “a state of wellbeing in which every individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (WHO, 2014). This definition brings to focus two core points that allow mental health to be properly understood: First, mental health is not just a state whereby an individual is free from any mental disorders. Second, positive mental health is the cornerstone of a person’s wellbeing, as it governs the effective functioning of each and every aspect of life (emotional, physical and social). It enables the individual to cope with stress and thrive in the workplace, leading to positive growth and contributions towards society. A positive mental wellbeing is not just an asset for the employee, but for the organisation and the country, considering the resulting economic and social impacts healthy employees can bring collectively.

Challenges in Today’s Workplace

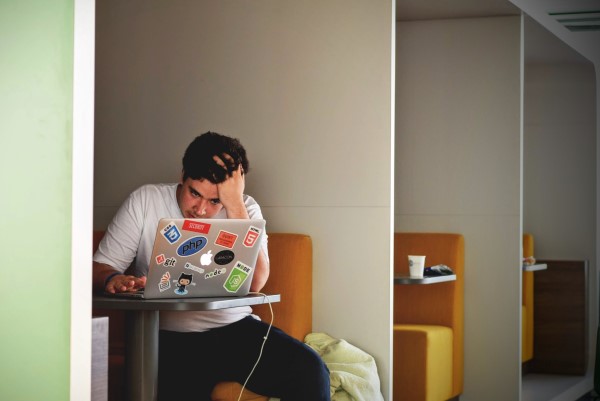

A working person spends a considerable amount of time at the workplace, and is greatly influenced by the experiences encountered in the course of work. Moreover, many employees do not leave work behind after office hours, as their work and experiences from work often accompany them home. It is no wonder that work stress often infiltrates the home even while employees switch hats to perform familial roles. The situation is further exacerbated by technological advances and the availability of flexible work arrangements, enabling employees to work from multiple locations at different times. For example, the use of video conferencing via laptops or mobile phones allows employees to work from anywhere and at any time, holidays included. Technology is a double- edged sword; while improving productivity and simplifying processes, the ability to work on the go creates new expectations such as prompt response time, thereby adding to work stress.

Feeling the Pulse: Workplace Surveys on Mental Wellbeing

Singapore was a fishing village before it was colonised by the British in 1819 and later gained independence in 1965. Many of Singapore’s laws are inherited from the British. There is considerable religious freedom, and the population observes faiths which originated from both East and West, like Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam and Taoism. Ours is a multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multi-lingual society. Among the resident population, the largest ethnic group is Chinese (74.3 per cent), followed by Malays (13.4), Indians (9.1) and others (3.2) (Statistics Singapore, 2017). The workforce is a microcosm that reflects such diversity, and its uniqueness means that many of the mental health concepts and interventions practised by its Western counterparts may not be relevant or applicable here. There are, nonetheless, common concerns faced by the workforce here, as surveys revealed.

A 2012 survey conducted by JobsCentral in Singapore revealed that over 80% of working adults reported increased stress level over a period of six months, as many employees value career as one of the top priorities in their lives while employers, faced with increasing manpower costs, demand higher productivity from their employees. Further surveys conducted by Singapore’s Health Promotion Board (HPB) found that the mental wellbeing scores of working Singaporeans are lower than those of the general population by 13 per cent, yet only 40 per cent of 12,000 small-and-medium enterprises (SMEs) expressed a willingness to invest in the mental wellbeing of their employees although most of them recognise the benefits of such investment. The reasons notably were lack of knowledge and resources. These surveys clearly point out one of the biggest challenges for Singapore companies, that there is no running away from mental health and stress issues for these are increasingly exerting a greater impact on employees’ productivity.

More recently, in 2017, the Aon’s Asia Pacific (APAC) Benefits Strategy found that in Singapore, 72 per cent of employers see mental issues as a concern, yet only 51 per cent have emotional and psychological wellness programmes in place; moreover, only 62 per cent of companies have plans to implement such programmes in the future, which is six points lower than the Asia Pacific average. In other words, nothing much has changed in the last few years with regard to addressing mental wellbeing at the Singapore workplace, which is a cause for concern given that it directly impacts on productivity.

Translating Knowledge into Practices

Although a lot of research has emphasised the importance of promoting employees’ wellbeing, little has been done to provide clarity to the process or mechanism. For example, many workplace interventions are not structured, targeting individuals sporadically, instead of being integrated into an organisation’s unique practices and processes. This brings into question whether the programmes pursued by companies to promote employees’ wellbeing are robust and far-reaching in impact. There appears to be a lack of effectiveness in workplace mental health intervention as well as lack of focus on the positive wellbeing of employees. People do not like to be treated like robots. A programme that evolves out of a genuine concern for their wellbeing has a greater chance for success than one that mechanically seeks to “increase productivity” or “create an ideal work environment” based on a certain formula.

Investing in Mental Health at the Workplace

Employee wellbeing has implications for both the employee and the organisation. An employee with low wellbeing trudges along, and weighs down others, with emotional and psychological burden: he or she is also less productive, makes poorer decisions, and contributes less to the organisation (Danna & Griffin, 1999). The reverse is true: when an employee’s wellbeing is at its optimum, he or she will be able to perform optimally at the workplace. When organisations pay attention to the employees by providing the necessary growth and positive factors to promote and support their wellbeing, a reciprocal relationship is created, and it bears fruits in the form of improved job performance. As mental wellbeing also directly affects how employees think and feel about their job and organisation (Tov & Chan, 2012), it is critical that employers focus on their employees’ mental wellbeing as a way for their organisations to grow.

Furthermore, mental and cognitive skills such as creativity, relationship and emotional skills, autonomy and exchange of knowledge (all of which are closely associated with the wellbeing of individuals), have been identified as key factors contributing to individual and collective efficiency within a company. Thus, these valuable skills can be tapped upon if the company can create conditions to increase employees’ wellbeing (European Network for Workplace Health Promotion, 2010).

An enlightened organisation will be quick to recognise that protection and support (through the right policies and interventions) will go very far in shaping up employees’ wellbeing. The effects will be transformational; the organisation moves beyond maintaining the status quo (it is no longer contented with just the absence of mental disorders), to a higher state where every employee has a relationship bond with his or her workplace. This can only be possible if every aspect of wellbeing (physical and mental) is addressed, and supportive policies and interventions enable employees to face up to their health concerns without fear of stigma and discrimination.

Moving Forward: The Search for Local Solutions

There is a pressing need for change in workplace culture that is supported by public education. Stakeholders such as policymakers and some forward-looking companies have helped to set things in motion. However, progress would be limited if not accompanied by tangible changes in public attitude, and this will take some time. More research, especially within the local context, is also needed. Besides creating awareness among employers and staff, research has the potential to develop suitable workplace mental wellbeing interventions that are grounded on common factors found in organisations here in Singapore. These factors consist of both risk and protective factors; they include (but are not limited to) organisational changes, organisational support, recognising and rewarding work, organisational justice, corporate climate, psychosocial safety climate, physical environment and stigma in the workplace (Harvey et al., 2014). The manner in which an organisation functions in each of the above mentioned factors can have important outcomes on the health and wellbeing of employees and eventually, organisational effectiveness.

It is important to note that organisation factors here may be different from those in the West. The notion of mental health itself differs widely across cultures and countries. Many of the perceived norms in highly-developed countries may be irrelevant; relying on them solely to guide our practices here in Singapore can be detrimental. Appreciating the historical context and the Asian cultural milieu is key. In many Asian countries for example, familial and traditional forms of care are often the preferred alternatives (Meshvara, 2002). Mental healthcare in the past was provided by family members together with religious persons in religious places such as temples, and this phenomenon persists into the modern era in these countries. Thus, improving mental health in Singapore requires a more holistic consideration of multiple relevant determinants such as historical, cultural and religious factors unique to our society, in the hope that culturally appropriate and evidence-based interventions (approaches and methods that have proven to be beneficial) can be recognised and implemented.

There is a lot of room in Singapore for the workplace mental health scene (in the areas of research and education) to expand, and expand we must as the stakes are high. A high level of mental wellbeing among the populace benefits employers, employees, and the society as a whole.

Chad Yip is a registered clinical psychologist who provides psychological assessment and treatment for children, adolescence and adults. He is also a clinical supervisor with the James Cook University, Australia (Singapore campus) clinical psychology team. Chad has received training in a variety of psychotherapeutic interventions and is trained in providing psychoeducational and neuropsychological assessments. His experiences also include working with the special needs, disadvantaged and forensic population